Spring is an exciting time that sets the stage for our annual planting season, a coordinated effort between many partners that results in billions of new oysters added to Maryland’s portion of the Chesapeake Bay! Enjoy a behind-the-scenes look in this five-part series, Planning for Planting.

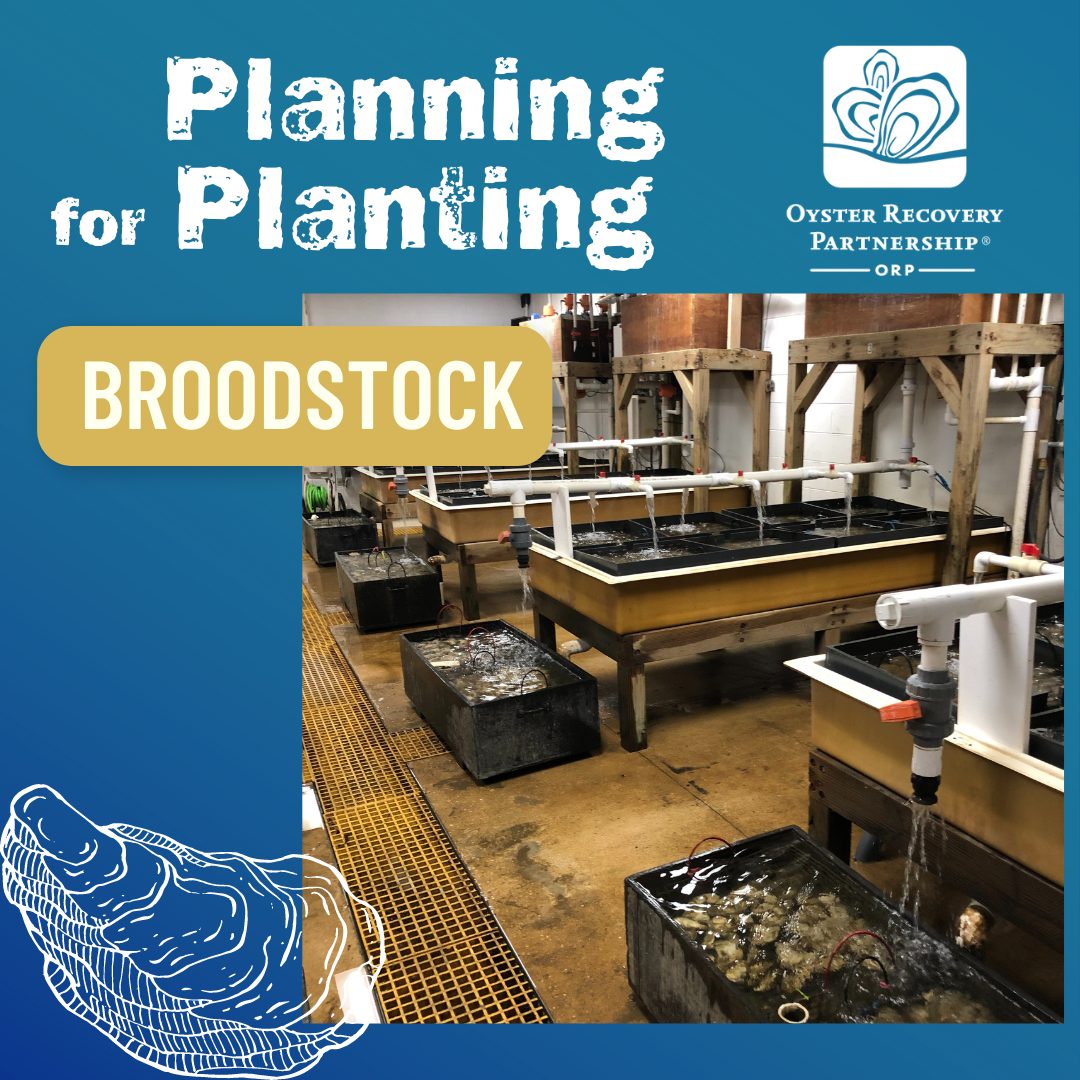

Part 1: BroodstockOysters pulled from local waterways are the unsung heroes in this process, as they are the “parents” of the juvenile oysters that result. Pulled from the wild in winter months by our partners at Horn Point Laboratory, these adult oysters are held in carefully controlled systems where hot and cold water from the Choptank River mimics springtime water conditions, encouraging the oysters to get ready to reproduce.

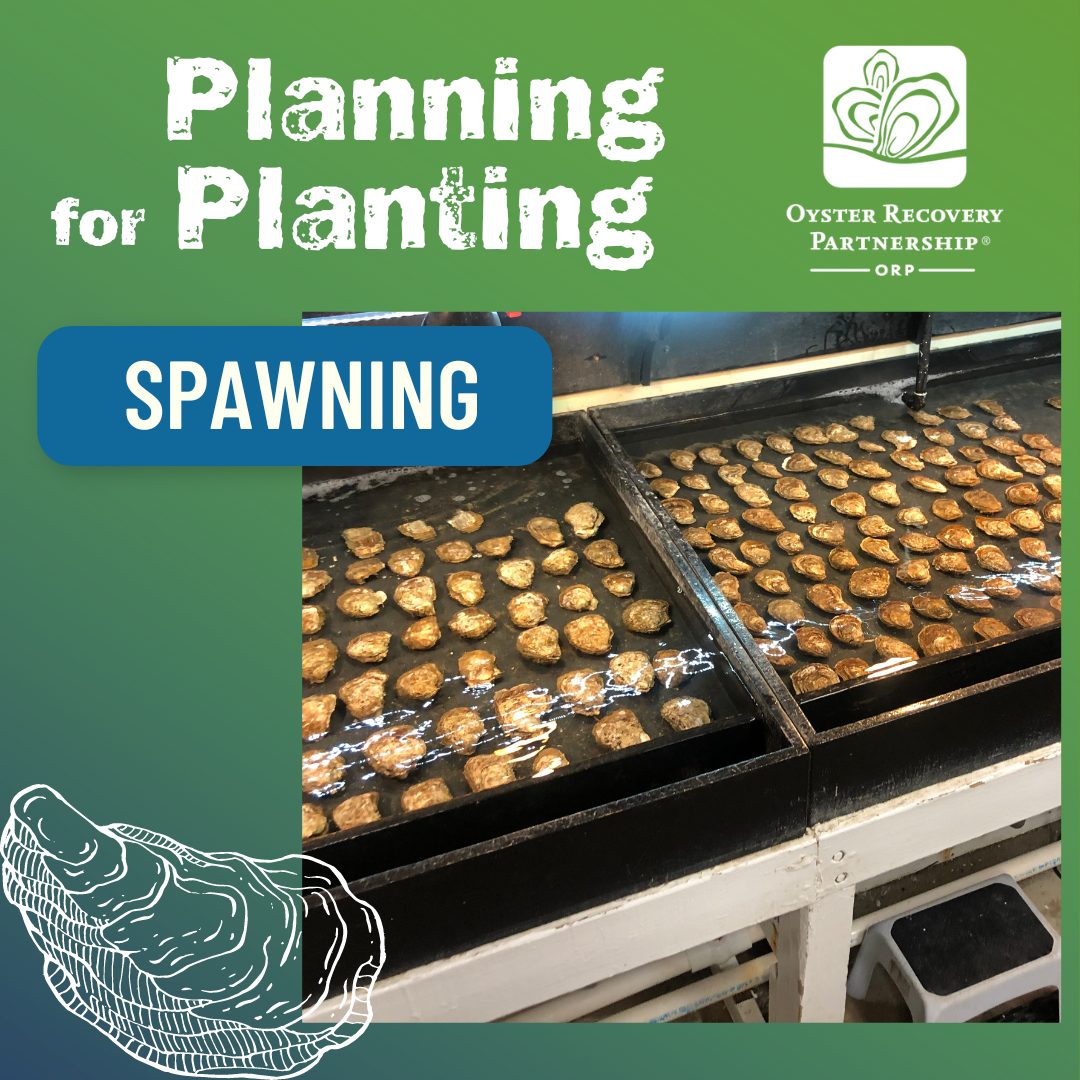

Part 2: Oyster SpawningOyster reproduction is an amazing process where all fertilization occurs outside the oyster in the water column. Once adult oysters are ready to spawn (or reproduce) they are placed on a table where warm water flows over them to simulate summer conditions. Females clap, releasing the eggs in a puff, while males release sperm in a continuous stream into the water. Horn Point Hatchery staff remove the spawning oysters from the table and place them into separate buckets to collect the eggs and sperm. Once the eggs are fertilized, they begin to develop into larvae. These larvae are transferred to large tanks to eat and grow… More from Horn Point demonstrating the spawning process…

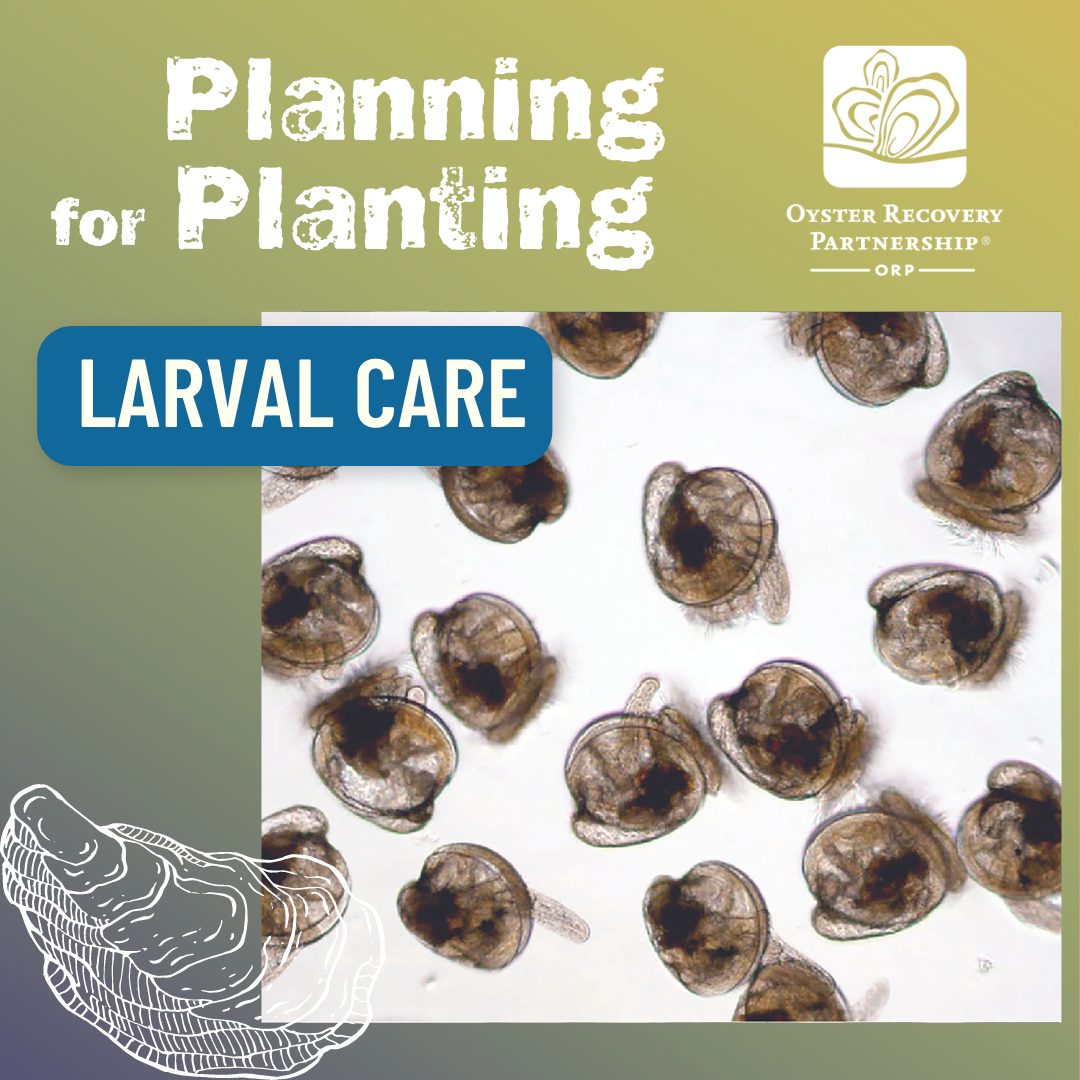

Part 3: Larval careOyster larvae swim freely in large, 10,000-gallon tanks as they grow. They are fed a carefully blended diet of different algae species or microscopic plants. After ~14 days, larvae develop an eye spot and a foot, indicating they will soon be ready to attach to a rigid substrate (like an oyster shell). Larvae are drained from the giant growing tanks and sorted by size. Not all larvae grow at the same rate. The larger, more mature larvae can be removed from the swimming culture and be bundled into a coffee filter for storage until they are needed for setting. The smaller larvae return to the tanks to continue growing until they mature.

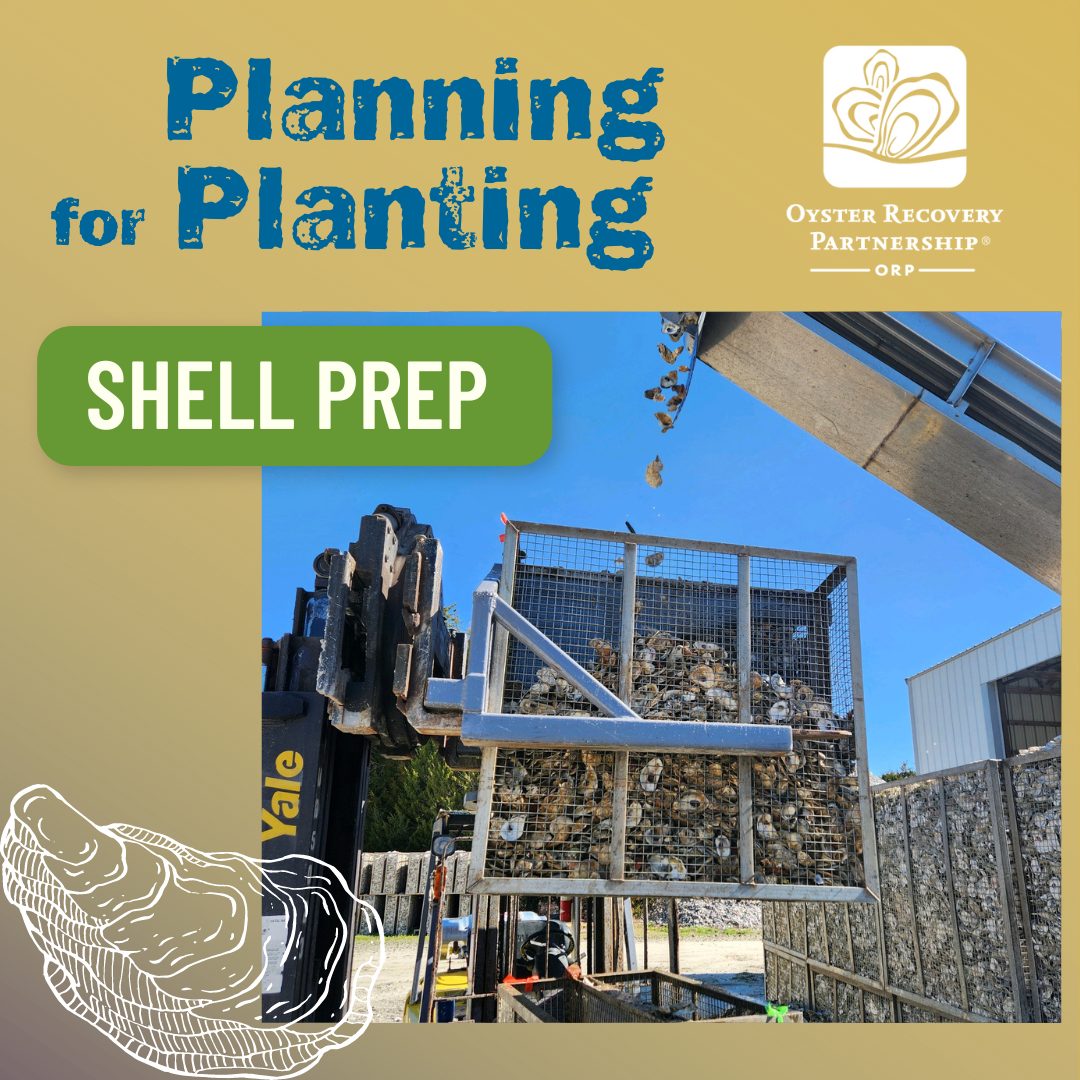

Part 4: Oyster Shell Collection and PreparationOyster shell is the best natural material for larvae to stick to, or “set on,” to grow into a mature adult. ORP’s Shell Recycling Alliance reclaims oyster shells for use in Chesapeake Bay oyster restoration by collecting shells year-round, free of charge, from restaurants and other seafood businesses throughout Maryland, DC, Virginia, and Pittsburgh, PA. This provides about 1/3 of the shell we need for restoration. We supplement the remainder by purchasing shells in bulk from oyster-shucking houses. The shell is aged outdoors for a year to remove organic material, then washed and placed into heavy-duty steel cages. Our hard-working field crew moves these cages to Horn Point’s setting pier. This video of our field crew moving and washing shell helps to visualize the process.

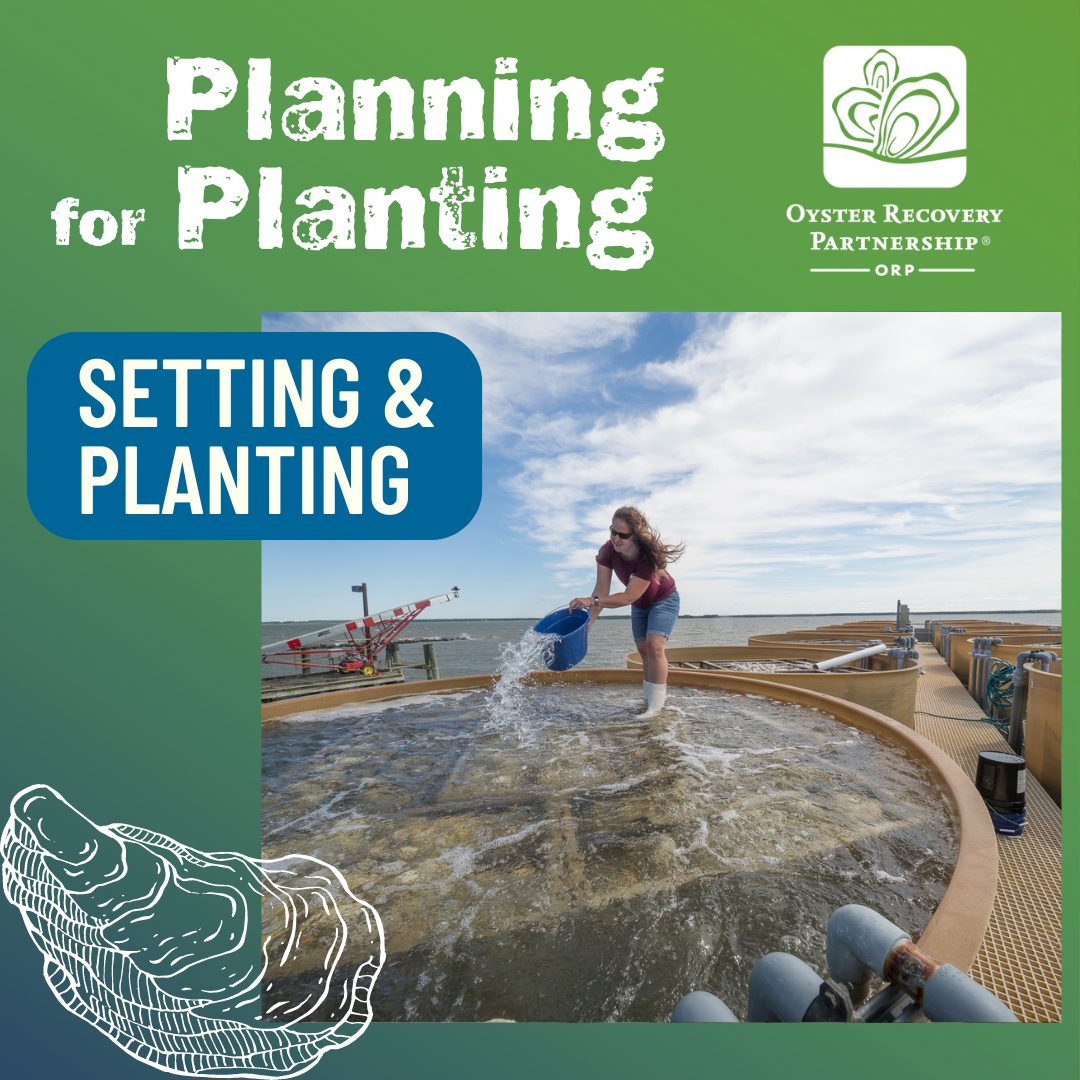

Part 5: Setting and PlantingMature larvae are introduced by Horn Point Laboratory staff into 52 tanks – each holding ~160 bushels of oyster shell – on the setting pier along the Choptank River. These larvae will attach to the oyster shell and metamorphose. Larvae get one shot at this process. Their future depends on connecting to one of the shells in these tanks. After about 48 hours, most larvae have glued themselves to a shell. They can no longer swim and are referred to as “spat-on-shell.” Once a tank of spat-on-shell has grown in ambient natural conditions for a week, the spat is ready to be transferred to its final planting site. ORP’s field crew unloads the tanks and transports the spat-on-shell to a boat to be planted in the Bay. This final step completes the extensive prep process! Watch a quick, 30-second video of what happens at the setting pier… Thank you to all of our partners who make oyster restoration possible, including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, and Maryland Watermen. |